One of my earliest food memories is from the terrible twos, when I subsisted almost exclusively on udon noodles and Nilla wafers. One morning, my mother hoisted my squirmy body onto her lap to feed me steamed white rice and tinned sardines, mashed together and seasoned with a dash of soy sauce.

In true Filipino form, she eschewed utensils for hands. Pinching the mushy mixture between her fingers, she aimed each babe-sized bite straight for my beak. These days, my go-to preparations — smoked oysters paired with a shard of Manchego or oil-packed mackerel flaked onto a hard-boiled egg — haven’t strayed far from the simplicity of my mother’s special recipe since the pull-tab pantry staple practically forbids fussy fare. My lifelong devotion to shelf-stable seafood is as deep as the ocean.

I wish I could say the same for my fellow Americans, but I grew up on sardines, not the American pantry pillar known as water-packed albacore, dry and flavorless by design thanks to early-1900s fishing technology that removed pungent fish oils to create a more familiar flavor and texture profile. This so-called “chicken of the sea” is widely blamed for the modern-day bias against canned tuna in the United States.

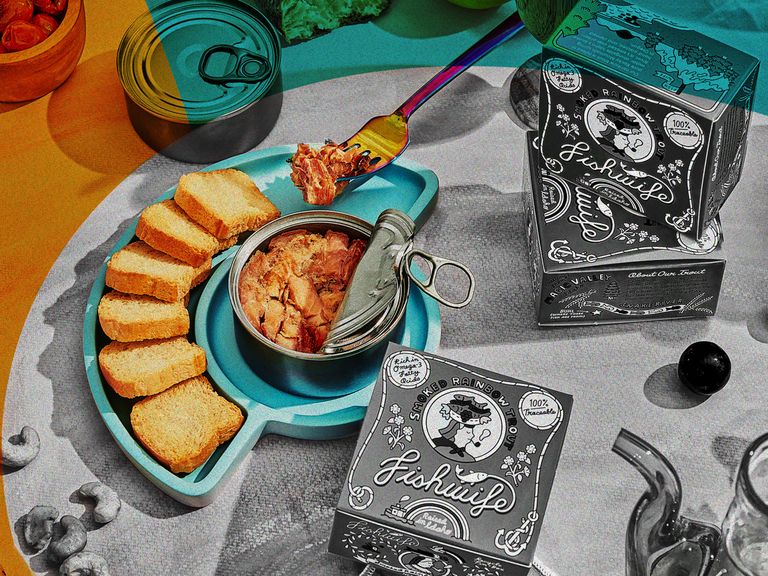

“It’s a commodity product that really took off in the Depression era and basically stayed there,” says Becca Millstein, CEO of Los Angeles-based Fishwife, a boutique line of tinned seafood. “It became something that you eat when you don’t have a lot of resources and need some protein.”

In contrast, Europeans have been cracking open jars and cans of preserved fish since 1795, leading inventor Nicolas Appert to pitch using it to feed soldiers in the Napoleonic wars to the French government. This also means that Europe is centuries ahead of the U.S. when it comes to evolving the craft and culture of canned seafood. In fact, Fishwife — a 16th-century slur for crass lasses — was inspired by the founder’s college-era stint studying in southern Spain, where canned seafood, called conserva, is incredibly chic.

“The conserva culture is beautiful, from its vibrant tins to the way it’s served with hard cheeses, pickled vegetables, bread, beer,” says Millstein, who formerly worked in the music industry in L.A. “It’s a humble but very sexy way of eating.”

Fishwife’s original delicacies — smoked tuna, salmon, and trout — are an easy entry point for the tinned-fish curious. The company has recently upped the flavor ante: Its newest tin, Cantabrian anchovies in Spanish olive oil, packs an umami wallop for snacking or seasoning, while a collaboration with Fly by Jing, a smoked salmon with Sichuan chili crisp, has become the line’s bestseller.

Like Millstein, when former fine-dining chef Sara Hauman launched Portland, Oregon-based Tiny Fish Co. at the peak of the pandemic, she strategically cast her net into an upswell in the global canned-seafood market, expected to be valued at $50.5 billion by 2030.

Hauman’s recipes — octopus with lemon and dill, rockfish with sweet soy sauce, and chorizo-spiced smoked mussels — are drawn from her early-career experiences cooking in southern Spain and the Basque region of France. “Across the globe, tinned fish is flavored with miso and curry and chorizo spices,” she says. “There’s a whole world of tasty, delicious morsels that most Americans have yet to discover.”

Far-flung flavor inspirations notwithstanding, Tiny Fish Co.’s sustainable harvest includes farmed bivalves that filter ocean water for food, eliminating the need for sketchy diet supplements, and “trash fish,” a term that woefully devalues less-marketable but still delicious bycatch like rockfish. In addition, these pelagic proteins are completely endemic to the Pacific Northwest, where all company operations are based. That means the unsung hero of this romantic “merroir” (the maritime equivalent of wine’s terroir, or sense of place) is a drastically reduced carbon footprint.

Like kelp billowing in the ocean, the sustainability factor and nutritional value of canned seafood are often intertwined. Commonly tinned small fish like sardines, anchovies, and mackerel are abundantly nutritious, rich in heart-healthy, brain-boosting omega-3 fatty acids; bone-densifying calcium; and selenium and iodine, champions of the immune system and thyroid.

Given a generous gap between harvests, these fish will repopulate with abandon. They also happen to be among the lowest-carbon animal proteins available, on par with roots, seeds, and nuts, according to Stanford research. They require only small, low-horsepower boats to travel about 10 miles offshore to swoop up a school. Considering the long distances required to transport livestock feed to ranches, beef is drastically opposite small fish on the spectrum of emissions from food, a category that accounts for one-third of the global greenhouse gases responsible for climate change.

But the buck doesn’t stop at food miles. How food is grown is also among the many considerations that go into calculating carbon footprints. While Fishwife sources from worldwide fisheries and aquaculture farms, they are rigorously vetted for their sustainability practices. The anchovies hail from a Marine Stewardship Council-certified fishery in the Cantabrian Sea, and the Atlantic salmon is sourced from Norway’s Kvarøy Arctic, an Aquaculture Stewardship Council-certified fish farm set between two fjords in the pristine waters of the Arctic Circle.

Working synchronously with nature is also valuable when considering the sustainability of seafood, whether it’s destined for tins or otherwise. (Pescavore, for example, offers jerky-like strips of fish in pouches for easy, protein-filled snacking.) “The truth is that tinned fish has allowed us to achieve a major goal of sustainable fishery management by harvesting from the right place in the ocean at the optimal time,” says Dan Creagan, who manages product development at Sausalito, California-based Patagonia Provisions.

Creagan's fondness for the company’s tinned mackerel only deepened on a recent trip to Galicia in northwest Spain. There, he observed the canning artisans at Conservas Antonio Pérez Lafuente — a family-run company with a coveted seal of approval from Friend of the Sea, a global certification for marine sustainability — painstakingly remove the bones and skin from wild-caught mackerel before delicately shingling the fish into the tin by hand. “In the final product," says Creagan, "you can taste all of that love and care."

Leilani Marie Labong is a San Francisco-based writer who has contributed to Elle Decor, Architectural Digest, Travel + Leisure, San Francisco Chronicle, and Coastal Living. Follow her on Instagram at @leilanimarielabong.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY